Scientists say they now have evidence suggesting a rabid raccoon hitchhiked more than 500 kilometres into Ontario from southeastern New York state to ignite Ontario's first rabies outbreak in a decade.

Susan Nadin-Davis, a researcher with the Canadian Food Inspection Agency who focuses on rabies research, said she was surprised at the result and had to run tests again to make sure it wasn't a mistake.

"I went back and re-analyzed the sample in order to confirm there hadn't been a mixup or cross-contamination," Nadin-Davis said. "The results seem to hold true. It was quite a surprise."

A fight between two Hamilton dogs and an aggressive raccoon in the back of an animal control van in December led to the discovery of the first documented case of rabies in a raccoon in the province since 2005.

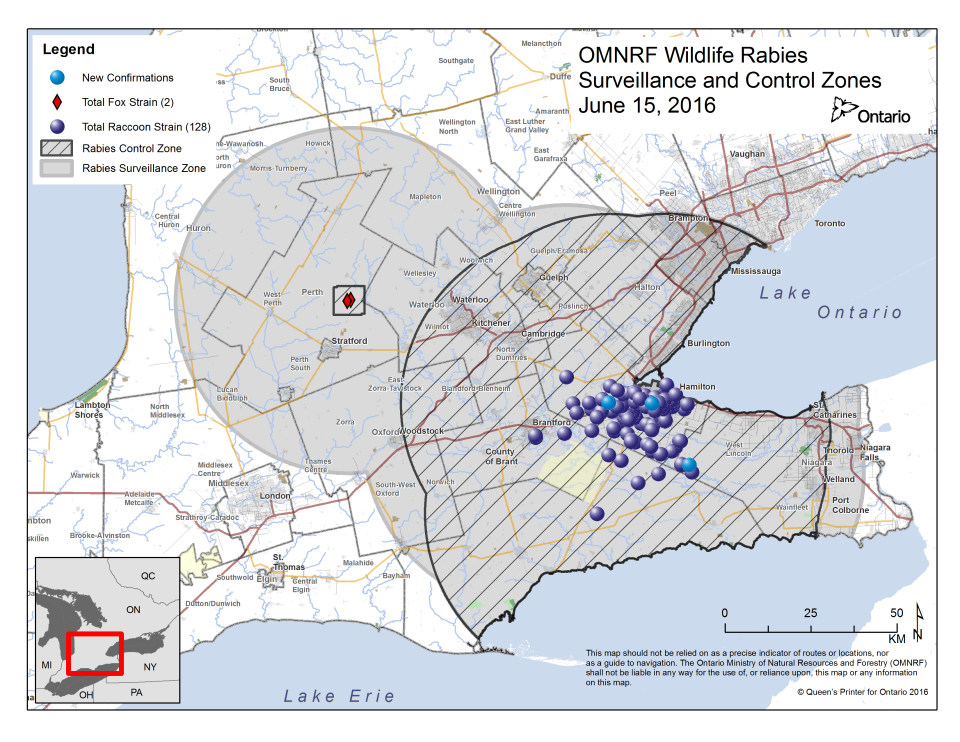

The outbreak has ballooned to 128 cases of raccoon strain rabies in both the masked creatures and skunks, according to the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, which is charged with managing the outbreak.

Nadin-Davis says her laboratory in Ottawa has genetically analyzed the rabies strain with a new technique and compared the results to a database she has been building for the past several years that helps pinpoint where variants of the virus originate.

She said the virus is closely related to a strain from southeastern New York state, and quite distinct from the strains found closer to the border.

Chris Davies, the ministry's head of wildlife research, praised Nadin-Davis's work.

"If we understand how rabies spreads, then we can identify tactics to prevent and reduce the chance of this happening again," Davies said. "If you don't know where it's coming from, how would you ever be able to do that?"

Nadin-Davis had expected the virus had come from "an incursion" from western New York state, where there are active rabies cases in raccoons, and was surprised it came from further afield.

But even with the presence of rabid raccoons closer to the Canadian border, they still would have faced a daunting task to bring the virus into Canada. Ontario has long had a nearly invisible barrier draped across its southern border that is designed to keep rabid raccoons away from their healthy Canadian brethren.

That barrier consists of thousands of edible rabies vaccine baits that have proven incredibly effective.

The CFIA's research has further galvanized the ministry's belief that its rabies vaccine, ONRAB, continues to work along the border.

"We don't know what it came on, but it was either a truck or a train," Davies said.

The ministry continues to carpet bomb a wide swath of southwestern Ontario with the vaccine, having dropped 600,000 baits since early April, Davies said.

They'll do it all again in the fall, where they hope to vaccinate young raccoons because the vaccine won't work until they reach 16 weeks old.

Nadin-Davis said she will use her research techniques to look into the role skunks are playing in the outbreak, which represent about 30 per cent of the cases that have tested positive for the virus.