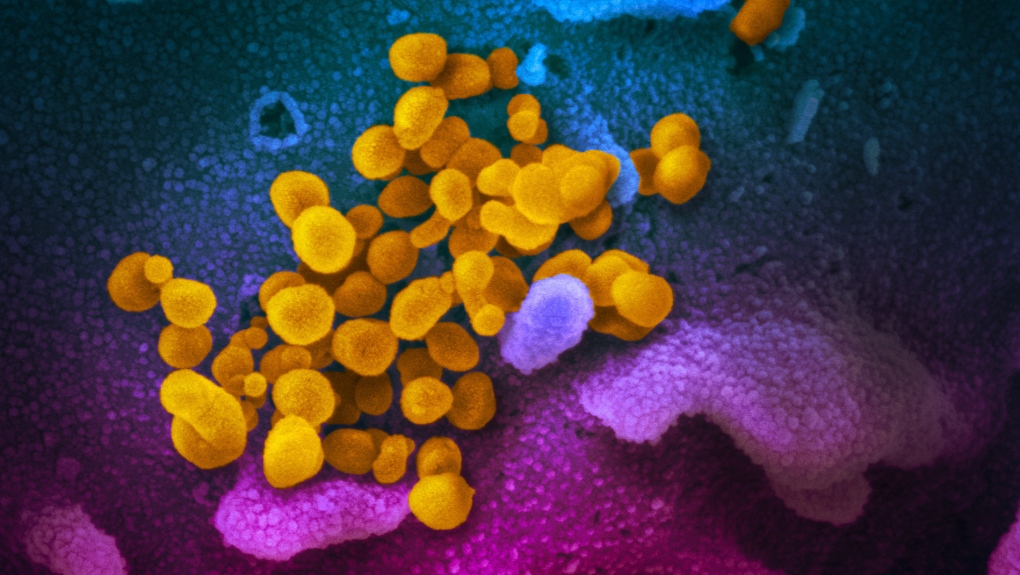

KITCHENER -- Researchers from the University of Waterloo and McMaster University are investigating how the virus causing COVID-19 gets into patients' lungs.

The researchers said SARS-CoV-2 usually enters cells through a receptor on cell surfaces, known as ACE2. The latest study by the McMaster-Waterloo team showed there are low ACE2 receptor levels in human lung tissue, the University of Waterloo said in a news release.

“Our finding is somewhat controversial, as it suggests that there must be other ways, other receptors for the virus, that regulate its infection of the lungs,” Jeremy Hirota, co-lead scientist of the team from the Research Institute of St. Joe’s Hamilton and an Assistant Professor of Medicine at McMaster, said in a news release. “We were surprised that the fundamental characterization of the candidate receptors in human lung tissue had not yet been done in a systematic way with modern technologies.”

Andrew Doxey, a biology professor from the University of Waterloo who is co-leading the study, said the low levels of ACE2 in lung tissue has "important implications" for the virus.

“ACE2 is not the full story and may be more relevant in other tissues such as the vascular system," Doxey said in a news release.

Their findings have been published in the European Respiratory Journal, and have been independently confirmed by other researchers in Molecular Systems Biology.

The university said the next step is to look at other infection pathways and how different patients respond to infection. Researchers use nasal swabs collected for COVID-19 diagnoses to look at genes expressed in patient's cells.

The researchers hope the study will help identify and treat patients who are at a higher risk of developing serious complications from the novel coronavirus and predict hospital capacity needs.

“It is clear that some individuals respond better than others to the same SARS-CoV-2 virus. The differential response to the same virus suggests that each individual patient, with their unique characteristics, heavily influences COVID-19 disease severity,” Hirota said. “We think it is the lung immune system that differs between COVID-19 patients, and by understanding which patients’ lung immune systems are helpful and which are harmful, we may be able to help physicians proactively manage the most at risk-patients.”

The researchers hope to use positive and negative COVID-19 tests to create algorithms on morbidity and mortality to help optimize health care.

They've received grants from the Ontario COVID-19 Rapid Research Fund and the COVID-19 Innovation Challenge.