How to experience April’s 'once-in-a-lifetime' eclipse

People watch a "ring of fire" solar eclipse in Tatacoa Desert, Colombia, Saturday, Oct. 14, 2023. The annular eclipse dimmed the skies over parts of the western U.S. and Central and South America. (AP Photo/Ivan Valencia)

People watch a "ring of fire" solar eclipse in Tatacoa Desert, Colombia, Saturday, Oct. 14, 2023. The annular eclipse dimmed the skies over parts of the western U.S. and Central and South America. (AP Photo/Ivan Valencia)

People in parts of Ontario have the chance to witness a rare celestial event this spring as a total solar eclipse casts sections of eastern Canada, the United States and Mexico into darkness.

It’s prompted several school boards to cancel classes out of fear students could damage their eyes looking at it.

So what makes this eclipse special and how can you view it safely? Here’s what you need to know.

How rare is the 2024 eclipse?

While solar eclipses happen every couple years in some part of the world, they are seldom seen in the same place.

- MORE: How to photograph a solar eclipse

- Teachers' union urges WRDSB to reconsider plans for solar eclipse

According to the Kitchener-Waterloo Chapter of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, the April 8 total solar eclipse will be the first in this area since 1925 – and there won’t be one again until 2144.

“It’s a legitimate once-in-a-lifetime opportunity,” says Orbax, a science communicator for the University of Guelph’s physics department.

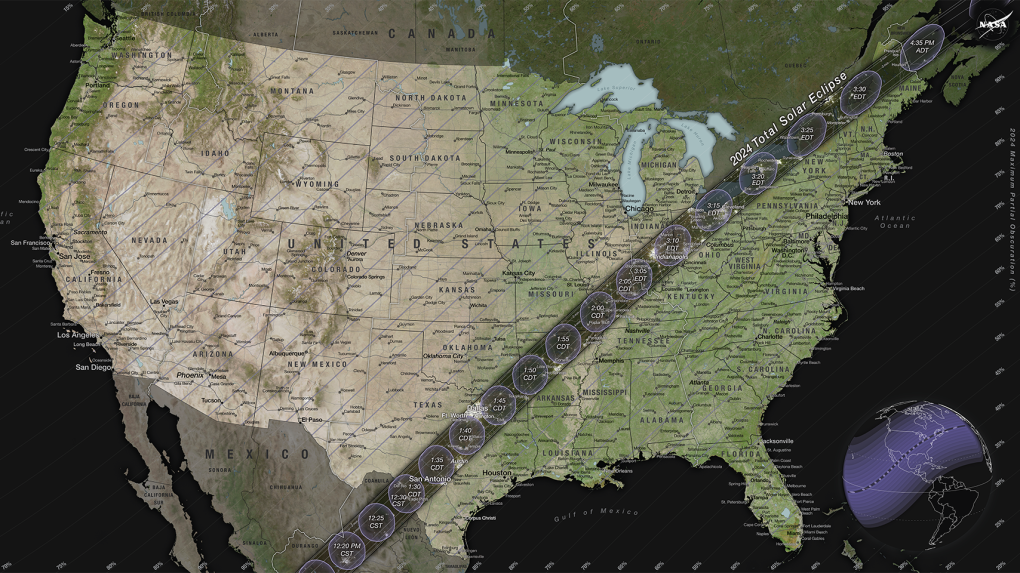

A map shows the path of the April 8, 2024 total solar eclipse. (NASA)

A map shows the path of the April 8, 2024 total solar eclipse. (NASA)

What is a solar eclipse?

A solar eclipse occurs when the moon passes between the earth and the sun, blocking the sun’s light from reaching part of the earth.

“This is a fairly rare thing because the Moon is about 400 times smaller than the sun, but the sun's about 400 times further away from us than the moon is. So it's a really strange coincidence that these two things align at this moment where one blocks the other,” Orbax explains, noting earth is the only planet in our solar system that experiences solar eclipses because although other planets have moons, they’re not the right size to blot out the sun.

The moon covers the sun during a total solar eclipse in Piedra del Aguila, Argentina, Monday, Dec. 14, 2020. The total solar eclipse was visible from the northern Patagonia region of Argentina and from Araucania in Chile, and as a partial eclipse from the lower two-thirds of South America. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

The moon covers the sun during a total solar eclipse in Piedra del Aguila, Argentina, Monday, Dec. 14, 2020. The total solar eclipse was visible from the northern Patagonia region of Argentina and from Araucania in Chile, and as a partial eclipse from the lower two-thirds of South America. (AP Photo/Natacha Pisarenko)

Where to see the eclipse

During the April 8 eclipse, the moon will block out around 99 per cent of the sun in Kitchener and Guelph. Online eclipse simulators give an idea of how it will look.

But just to the south, the sun will be entirely obscured. Areas where the sun temporarily won’t be visible at all form what’s called the “path of totality.”

“I hate saying this, because if you’re not in totality, you should never do this and it’s unsafe, but in totality, you can actually remove your eclipse glasses because all of the sun's light is blocked,” Orbax says. “So you can actually look upon that blacked sun and just see the little wisps of light kind of peeking out of the edge of it.”

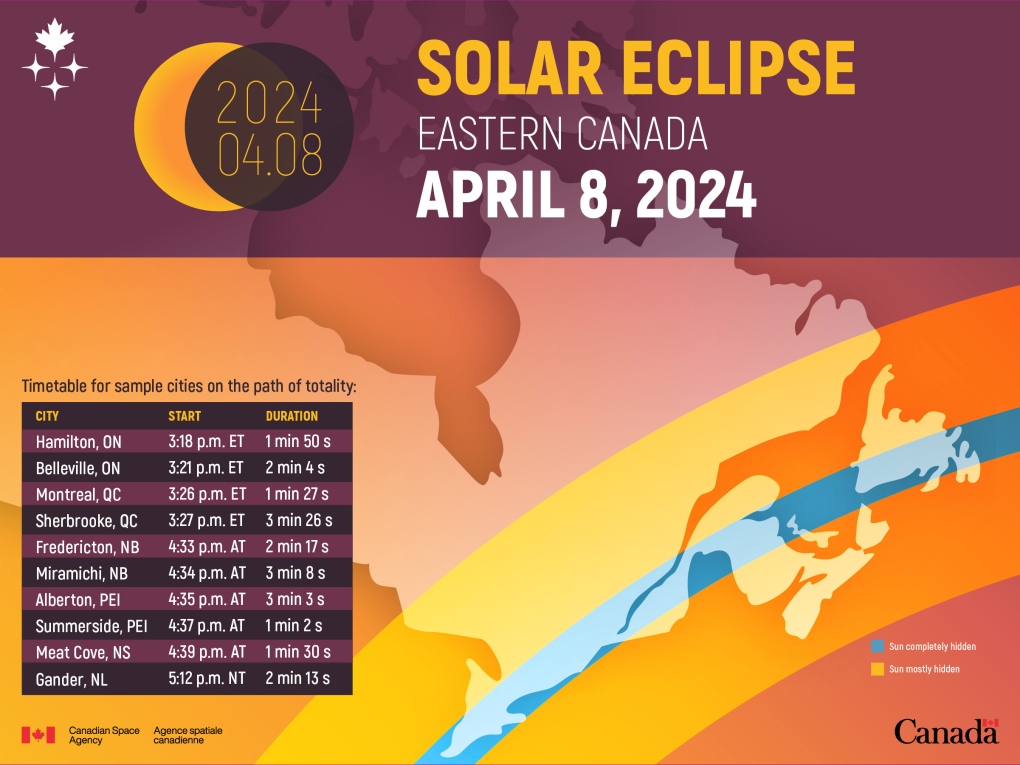

Hamilton will experience totality for one minute and 50 seconds starting at 3:18 p.m., according to the Canadian Space Agency.

Niagara Falls, will be in totality for around three minutes and 30 seconds.

Jan Cami, an astronomy professor at Western University says it will be worth fighting possible traffic jams to view from areas in the path totality.

“The difference, I can tell you, between a 99.9 per cent partial eclipse and a total solar eclipse is literally the difference between day and night,” Cami told CTV London.

In southern Ontario, the moon will begin moving across the sun, appearing to cast a shadow on its surface at around 2 p.m. The eclipse will end around 4:30 p.m.

Why is it dangerous to look at a solar eclipse?

You shouldn’t look at an eclipse without eye protection because staring directly at the sun can seriously damage your eyes.

The sun is no more powerful than usual during an eclipse. But because an eclipse causes the sky to darken, some people might think it’s safe to look directly at the sun – it’s not.

“You’re not supposed to look at an eclipse because you’re not supposed to look at the sun,” Orbax explains. “The thing is people say ‘oh it’s dark, I could stare at the sun for a bit.’ Don’t stare at the sun. Hopefully that’s common sense.”

NASA’s guide to solar eclipse safety, outlines how to observe one without damaging your eyes.

Use solar viewing glasses, known as eclipse glasses, or welding glasses. Regular sunglasses, no matter how dark, are not safe for viewing the sun, NASA says.

Do not look at the sun through a camera lens, telescope, binoculars, or any other optical device while wearing eclipse glasses or using a handheld solar viewer — the concentrated solar rays will burn through the filter and cause serious eye injury.

A group of people watch a partial solar eclipse at the Frost Science Museum on Saturday, Oct. 14, 2023, in downtown Miami. (Matias J. Ocner/Miami Herald via AP)

A group of people watch a partial solar eclipse at the Frost Science Museum on Saturday, Oct. 14, 2023, in downtown Miami. (Matias J. Ocner/Miami Herald via AP)

Ultimately, Orbax says you don’t need a lot of equipment or predefined knowledge to take in the beauty of the eclipse.

“Anybody can experience this by just getting a pair of glasses or viewers and looking up and taking a look at what's going on in the cosmos. And I think it's an incredibly humbling experience to gaze up and realize that we're just tiny little creatures on a great big rock that's floating through space around a bunch of other rocks that are all being lit and given warmth from this big nuclear explosion in the sky,” he says.

“I think to me, it makes some of the problems and the issues that we have down here seem a little bit insignificant when you look at the grandiose scope of something like this.”

For people who want to take a deeper dive into the science behind the eclipse, the University of Guelph Physics Department will be putting out a series of videos on the phenomenon in the coming weeks, Orbax adds.

With files from Sean Irvine, CTV News London

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Prime Minister Trudeau meets Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau landed in West Palm Beach, Fla., on Friday evening to meet with U.S.-president elect Donald Trump at Mar-a-Lago, sources confirm to CTV News.

'Mayday! Mayday! Mayday!': Details emerge in Boeing 737 incident at Montreal airport

New details suggest that there were communication issues between the pilots of a charter flight and the control tower at Montreal's Mirabel airport when a Boeing 737 made an emergency landing on Wednesday.

Hit man offered $100,000 to kill Montreal crime reporter covering his trial

Political leaders and press freedom groups on Friday were left shell-shocked after Montreal news outlet La Presse revealed that a hit man had offered $100,000 to have one of its crime reporters assassinated.

Questrade lays off undisclosed number of employees

Questrade Financial Group Inc. says it has laid off an undisclosed number of employees to better fit its business strategy.

Cucumbers sold in Ontario, other provinces recalled over possible salmonella contamination

A U.S. company is recalling cucumbers sold in Ontario and other Canadian provinces due to possible salmonella contamination.

Billboard apologizes to Taylor Swift for video snafu

Billboard put together a video of some of Swift's achievements and used a clip from Kanye West's music video for the song 'Famous.'

Musk joins Trump and family for Thanksgiving at Mar-a-Lago

Elon Musk had a seat at the family table for Thanksgiving dinner at Mar-a-Lago, joining President-elect Donald Trump, Melania Trump and their 18-year-old son.

John Herdman resigns as head coach of Toronto FC

John Herdman, embroiled in the drone-spying scandal that has dogged Canada Soccer, has resigned as coach of Toronto FC.

Weekend weather: Parts of Canada could see up to 50 centimetres of snow, wind chills of -40

Winter is less than a month away, but parts of Canada are already projected to see winter-like weather.