Staccato scenes play out in Jody McLennan's mind on loop: her husband slumped in his chair, paramedics pumping his chest, his lifeless body splayed on their living room floor.

Only four hours earlier, McLennan and Oghenovo Avwunufe had been munching on chips and drinking beer before she fell asleep on the couch while he sat in front of the computer, working on a business project. Unbeknownst to McLennan, Avwunufe had snorted cocaine earlier with a friend.

He was still in the same chair when McLennan woke up at 6 a.m., she recalled in a recent interview.

"I thought he was sleeping, so I went over and shook him, and I knew when I shook him that he wasn't alive," she said.

Paramedics arrived within minutes and immediately began pumping Avwunufe's chest, but they were unable to revive him. A coroner arrived about five hours later and pronounced the 25-year-old dead.

The coroner told McLennan her husband's blood was sent to the Centre for Forensic Sciences -- the scientific arm of Ontario's justice system -- for a toxicological analysis. Once the results were in -- the turnaround time is 37 days, according to the lab -- the coroner would determine the cause of death and notify the victim's family. The whole investigation takes months to conduct, according to a spokeswoman for Ontario's Office of the Chief Coroner.

It's been nearly two months since that morning on Feb. 12 and McLennan said she's still waiting for official word on what killed Avwunufe, a recreational drug user.

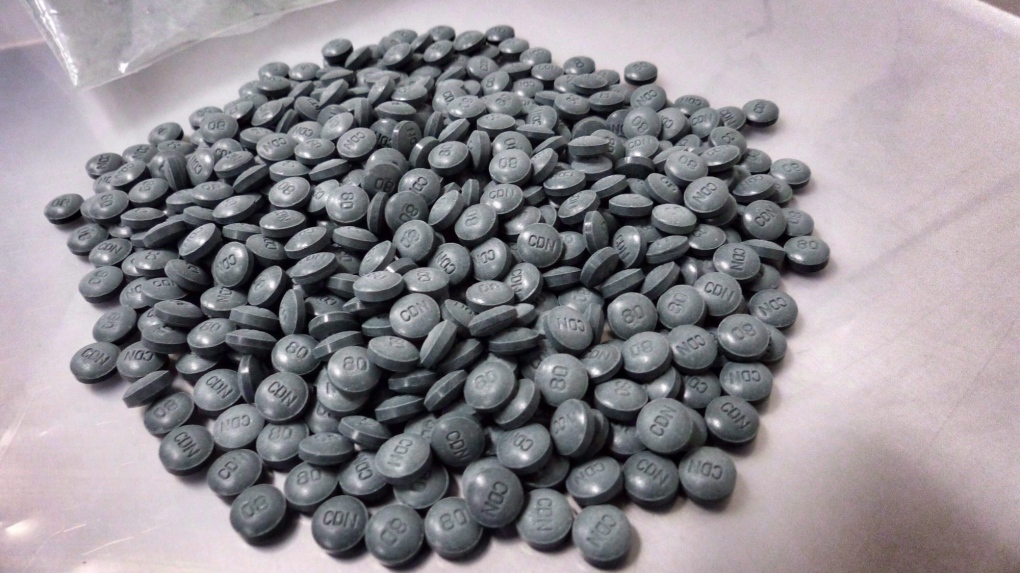

Toronto police said they found white powder near Avwunufe's body and sent it to Health Canada for urgent testing on Feb. 14. Const. Victor Kwong said the force learned one day later that it contained cocaine, caffeine and fentanyl, a synthetic opioid roughly 100 times more potent than morphine that is increasingly being found in street drugs.

The often months-long wait for results of toxicology and drug tests involving fentanyl in Ontario is a major concern not just for victims' families, but also for the province's police forces and health units who say they require good and current data to plan public outreach and enforcement.

The lack of up-to-date statistics on opioid-related deaths and overdoses has now left police and health units struggling to come up with their own tracking methods for fentanyl.

The Toronto Board of Health, at a meeting on March 20, called for expedited development of a provincial overdose surveillance and monitoring system.

"The truth is we do not have good data," said Susan Shepherd, manager of the Toronto Drug Strategy with the city's public health unit. "One of the things we don't know is non-fatal overdoses, which happen a lot. And there is about a two-year lag on death data."

Rick Barnum, a self-described "drug cop" who worked undercover with provincial police when crack cocaine use exploded in Ontario in the 1990s, said getting more data faster would help focus the provincial police's efforts on fentanyl.

"I think it's absolutely vital that we get our tests back as quickly as possible to understand exactly what our officers and the public are dealing with out there," said Barnum, who is now deputy commissioner of the Ontario Provincial Police.

"It's pretty hard to make an effective enforcement strategy or an effective treatment strategy or philosophy when you're always working six months, at least, behind."

The most recent data on Ontario opioid-related deaths is from 2015, when 166 people died from fentanyl toxicity -- more than double the number from five years earlier -- according to the Office of the Chief Coroner.

In October 2016, the province's Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care designated Dr. David Williams, the province's chief medical officer of health, as Ontario's first overdose co-ordinator and tasked him with launching a surveillance and reporting system to better respond to opioid overdoses.

Williams refused an interview with The Canadian Press to explain the province's progress on the opioid crisis, but spokesman David Jensen said the ministry "recognizes the pressing issue of problematic opioid use in Ontario."

On April 1, hospitals in the province began tracking opioid overdoses in their emergency departments on a weekly basis.

"Every hospital and public health unit will have access to near real-time data, giving experts a more comprehensive understanding of what's happening on the ground," Jensen said.

He said Williams has convened an advisory committee -- including public health, the medical community, law enforcement and paramedics -- that's working to examine early warning and risk management systems to enable Ontario to detect and respond to critical situations associated with illicit opioids.

That includes compiling information on laboratory capabilities to understand provincial testing capacity, Jensen said.

Many health units and police forces in Ontario point to British Columbia, a province that has borne the brunt of the opioid crisis and where the Coroners Service releases monthly reports on overdose deaths. In B.C., drugs such as fentanyl and the much stronger opioid carfentanil are tracked through doctor-ordered urine tests done by a private lab on addicts and those who are prescribed fentanyl for pain. Those tests can be done in two to three days.

"They're a good early-warning sign because they're the ones consuming the drugs on a regular basis," said Thomas Marshall, director of government relations for the privately operated LifeLabs.

Marshall said the information is shared with a group that includes officials from the Ministry of Health, the RCMP, the BC Centre for Disease Control, and the BC Centre for Substance Abuse.

On the policing side, a spokesman with Vancouver police said the force can get a rush analysis of seized drugs from Health Canada in one to three days, while regular analysis takes two months or more.

"Our Burnaby-based Health Canada lab has been very supportive with analysis during the fentanyl crisis," said Staff Sgt. Randy Fincham.

Health Canada spokeswoman Suzane Aboueid said samples are analysed on a first in, first out basis.

"Health Canada's Drug Analysis Service (DAS) returns results to the submitting officer within a 60-day service standard," Aboueid said, adding it can provide analysis results in two business days, when necessary.

"In light of the growing number of fentanyl cases, DAS is working in collaboration with police forces to meet their needs and address their turnaround time requirements."

In Ontario, some health units are not waiting for the provincial government to roll out its opioid strategy.

Hamilton's public health unit publishes weekly reports on opioid-related data they have begun collecting. Paramedics have created a category in their database to track suspected and confirmed opioid-related overdoses and administrations of naloxone, an opioid antidote. Between Jan. 10 and March 26, paramedics received 77 calls related to opioid overdoses. They said 79 per cent of the overdoses involved men with an average age of 36 years old.

"We're trying to get a picture of the opioid problem here, and we need data to get that," said Dr. Jessica Hopkins, the associate medical officer of health in Hamilton.

A public health unit in southwestern Ontario is in the midst of gathering similar data after crunching numbers that showed the rate of opioid-linked deaths in the Windsor, Ont., area was more than double the provincial rate in 2015.

Dr. Wajid Ahmed, associate medical officer of health with the Windsor-Essex County Health Unit, suspects fentanyl is playing a big role in overdoses in the area, but cannot say that conclusively.

"There is a lack of data throughout the province in general," Ahmed said.

Because of that data void, Ahmed said the unit is trying to get "frontline" numbers from doctors, hospitals, paramedics and pharmacies about fentanyl and other opioids to get a more fulsome, timely picture.

Meanwhile, Barnum said the OPP has developed its own system for tracking fentanyl using overdose reports from paramedics.

Fentanyl is "a whole different level of addiction," he said, noting that the drug has affected every area of the province.

Many of the victims are casual drug users like Avwunufe, who may not know that fentanyl is now being cut into many drugs, including cocaine and heroin, that are sold on the street.

Avwunufe's friend, Justin Meecham, said the pair had "dabbled" with cocaine that February night.

"I did two bumps and, boom, my head hit the table shortly after," said Meecham, who woke when the paramedics were trying to revive his friend.

"I woke up and he didn't. It's opened my eyes -- I haven't had a bump since. I had no idea fentanyl would be in cocaine."