Fighting for change: Victims of violent crime feel let down by prison and parole systems

This is the last of a three-part series looking at crime, the lingering effects of that trauma and what families are doing to try to change Canada’s justice system. The mothers of Bradley Pogue and Jeffrey Maxner have shared their heartbreaking stories and, in this final part of the series, we look at the current state of the parole system and the criteria for who gets early release.

Violent crimes often make headlines, but after sentencing, they tend fade from public view.

That is, until the offender makes a major move.

In June 2023, the transfer of serial rapist and killer Paul Bernardo to a medium-security prison sparked outrage across the country. The Correctional Service of Canada (CSC), citing privacy rights, provided no explanation for the move.

Another decision by the CSC, to transfer Michael Rafferty and Terri-Lynne McClintic to lower-security prisons, also shocked many Canadians in 2018. Both had been convicted for the kidnapping, rape and murder of eight-year-old Tori Stafford in 2009.

Tori’s father, Rodney Stafford, told the media at the time that he wanted increased transparency around the incarceration of his daughter’s killers, especially when it comes to parole. The families of victims, he added, deserved more respect.

“We don’t have any rights,” Stafford said. “They’ve been eliminated.”

Demanding answers

As detailed in parts one and two of this series, Hayley Schultz and Joanne Maxner also feel left out of the process.

That, seemingly, won’t be changing anytime soon.

Canada’s top court decided this week not to hear arguments around the release of Bernardo’s prison and parole documents, ending a years-long battle by the families of his victims to learn more about his prospects for parole. Both the CSC and Parole Board of Canada had previously denied thefamilies’ access-to-information requests.

An appeal court ruling, in July 2023, stated that the families wanted information that ranged “from the trivial to the intensely personal.” It called those requests a “total invasion” of the prisoner’s privacy.

“Bernardo, my guess is, will never be released,” criminologist Anthony Doob told CTV News after the transfer became public in 2023. “But most prisoners will be, and it’s [CSC’s] responsibility to make them into people who can be released.”

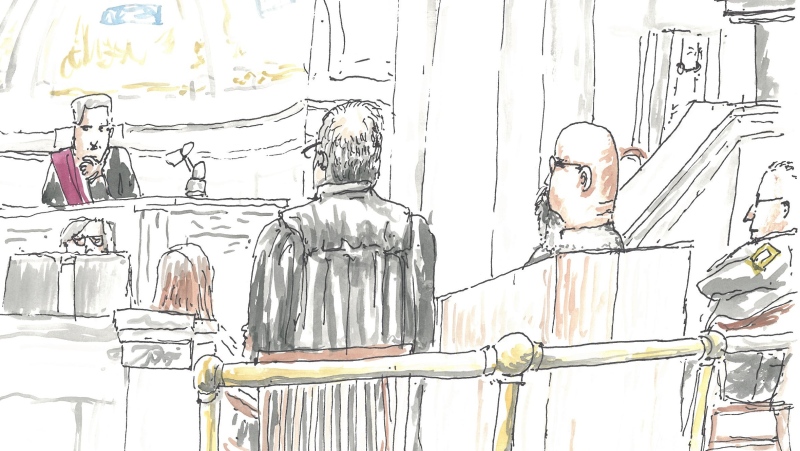

Paul Bernardo arrives at the provincial courthouse in the back of a police van in Toronto in a Nov. 3, 1995, file photo. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Frank Gunn

Paul Bernardo arrives at the provincial courthouse in the back of a police van in Toronto in a Nov. 3, 1995, file photo. THE CANADIAN PRESS/Frank Gunn

To get a better understanding of this process, CTV Kitchener spoke with Sarah Turnbull, an assistant professor in the department of sociology and legal studies at the University of Waterloo. Details of Pogue’s and Maxner’s cases were not shared with Turnbull, so she shared her insights as someone who has independently studied the parole system.

Understanding the parole system

Most offenders are eligible for full parole once they’ve completed one-third or seven years of their sentence, whichever comes first.

Full parole means offenders can serve out the remainder of their sentence in the community. While they can live on their own, they must regularly report to a parole officer. If they fail to meet the conditions of their release, however, it can be revoked.

For day parole, most are eligible six months prior to their eligibility for full parole. Offenders can seek employment, volunteer or pursue studies, but must return to their community-based residential facility at the end of each day and regularly meet with a parole officer.

When considering parole, the board looks at several factors including:

- Offender’s social and criminal history

- Reasons for and the type of offence

- Offender’s understanding of their crime

- Progress made by the offender including participation in programs behind bars

- Offender’s behaviour while in prison

- Victim impact statements

- Release plan and post-release community management strategy

Most importantly, parole is not guaranteed.

Why have a parole system?

“Canada generally does not practice indeterminate or indefinite sentencing,” Turnbull explained. “We hope people will eventually get out of prison, even lifers.”

It’s seen as an important step in an offender’s rehabilitation.

“The logic of the parole system is that they’re more likely to be successful if they are subject to supervision and have a gradual release where they can practice, essentially, their freedom in the community,” Turnbull said.

Offenders are supposed to, in theory, get the support they need to succeed. That includes checking into a halfway house, a community program and reporting back to a parole officer.

“They have the chance to find housing, work or go to school, and address issues that they might have like addictions or mental health counselling,” Turnbull said.

The research seems to back this up.

According to the Government of Canada, studies show offenders released under supervision are better able to reintegrate into the community. They’re also less likely to reoffend than those that serve out their full sentence.

“There’s a lot of myths about parole like reoffending rates are really high, which they’re not,” Turnbull explained. “Parole officers are required to monitor their behaviour. If people are breaking their release conditions, parole revocation means that the person has to come back to the prison.”

There are also other considerations, like cost.

“It’s expensive to hold people,” Turnbull said. “It’s much cheaper to supervise them in the community.”

A 2018 report from the Parliamentary Budget Officer looked at figures from 2016 and 2017. It showed the cost to house female inmates was $230 a day, or $83,861 a year. For male inmates in maximum security, it was $254 a day, or $92,740 a year, while males in minimum and medium security cost $47,370to $75,077 a year.

“Parole is really not talked about at all in Canada unless something goes wrong, where someone is not happy about a release decision,” said Turnbull. “It’s also difficult because the parole board is doing what is in the legislation.”

Conversations surrounding parole, meanwhile, have changed dramatically in recent years.

“Greater attention is being paid to victims and the impact of a parole decision. Victims can play a bigger part than previously in the past,” Turnbull explained. “[But] it’s also coincided with a ‘tough on crime’ mentality where the solution is more punishment.”

That begs another question.

“What does justice look like, and how do you achieve justice, if the person you’ve lost is never coming back?”

Punishment versus justice

It’s easy to take a black and white view of the justice system.

“We watch a lot of shows [where] the cops take away the bad guy and we sort of live happily ever after,” explained Turnbull.

It becomes a lot more difficult when the system has to settle on a verdict.

“How does a system of punishment equate [the loss of life] with a sentence? What does justice mean when you have had a loved one taken from you through a violent offense? As a culture, we’re socialized that prison is the solution to those sorts of problems. But then we also have a system where people get out of prison,”Turnbull said.

Punishment isn’t the same as justice, and for many victims of violent crime, no sentence will ever feel enough.

Turnbull’s view of the prison and parole system is from an academic perspective.

“I’ve argued that there’s not a lot of justice there,” she explained. “It doesn’t really help the person that did the offence. It doesn’t help the families and the loved ones of someone who has been murdered or killed.”

She also points to obstacles within the prison system, including inadequate support for mental health and addiction issues.

“I don’t think prisons solve the problems we have,” said Turnbull. “Decades of research show prisons are very harmful institutions. People are traumatized. They can come out worse than they went in. How do [offenders] reintegrate into society after they’ve served sentences?”

The parole system is set up to mitigate further criminal behaviour, but that doesn’t lessen the fears of families who have already been put through so much pain and loss.

Turnbull is sympathetic towards victims of violent crime, but feels the parole system does have some merit.

“Is it safer to release people gradually under supervision than just at the end of their sentence? Just open the prison gates and let someone go free? Once their sentence is complete, hopefully they are going to live law abiding lives and they do not commit future offences.”

Fighting for change

The men who killed Bradley Pogue and Jeffrey Maxner will both be eligible for parole in the near future.

For their mothers, it’s been too much, too soon.

They’ve been fighting to change the system for the last five years. During that time, they’ve had to grieve, come to terms with that loss, go through the emotional roller coaster of the court and sentencing process, and just when they’ve adjusted to their new normal, Hayley Schultz and Joanne Maxner have had to relive the worst days of their lives again in an effort to keep their sons’ killers behind bars.

Both men, they say, had criminal pasts before their incarceration. Schultz and Maxner worry that, without proper precautions in place, they’ll continue along that path.

What happens next to these men is out of their control, but doing something – anything – to change the system is the best way they know how to prevent other mothers from going through a similar heartbreak.

If you are struggling after experiencing a loss, please reach out to a local support group. You can also find additional information on the following websites:

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

NEW Is there a cost to convenience? Canada approves new cancer immunotherapy treatment

A new cancer treatment recently approved in Canada promises to cut treatment time down to just minutes, but experts have differing opinions on whether it's what's best for patients.

Air Canada walks back new seat selection policy change after backlash

Air Canada has paused a new seat selection fee for travellers booked on the lowest fares just days after implementing it.

Canada's new dental program offering hope of free care to millions but many dentists aren't signed up

A new Canadian dental care program is offering the hope of free care to millions, but while 1.7 million people have signed up for the plan, only about 5,000 dentists have done the same.

Province boots mayor and council in small northern Ont. town out of office

An ongoing municipal strike, court battles and revolt by half of council has prompted the province to oust the mayor and council in Black River-Matheson.

King Charles III returns to public duties with a trip to a cancer charity

King Charles III returned to public duties on Tuesday, visiting a cancer treatment charity and beginning his carefully managed comeback after the monarch's own cancer diagnosis sidelined him for three months.

NDP says Ottawa's new grocery task force isn't living up to government promises

The federal government says the task force it created to monitor and investigate grocery retailers' practices has not conducted any probes and doesn't have a mandate to take enforcement action.

A group of Toronto tenants have been on a rent strike for a year and say there's no resolution in sight

Dozens of tenants in Toronto's Thorncliffe Park area have now been withholding their rent for one year, and it’s unclear when the dispute will end.

U.K. police arrest man wielding a sword in east London, 5 people are taken to the hospital

A man wielding a sword attacked members of the public and two police officers on Tuesday in the east London community of Hainault before being arrested, police said.

Archeologists search for remnants of Halifax's 250-year-old wall that surrounded the city

Archeologist Jonathan Fowler is using ground-penetrating radar to search for historic evidence of the massive wall that surrounded Halifax more than 250 years ago.