In a bid to stop an outbreak of rabies that has now lasted for more than 18 months, the province is once again planning to leave bait packets containing the vaccine for the virus around southern Ontario.

Hundreds of cases of rabies have been confirmed in the area since December 2015, when a rabid raccoon was discovered in Hamilton.

While Hamilton has been considered ground zero for the outbreak of raccoon-strain rabies, positive tests for the virus have also come from the Haldimand-Norfolk and Brantford areas.

To the northwest, several cases of fox-strain rabies have been reported in an area stretching from Wallenstein to Blyth.

As a result, the province is planning an extensive campaign of airdrops and land drops of the rabies vaccine.

A rabies control zone has been established, encompassing virtually all of Waterloo-Wellington, Huron-Perth and Oxford-Brant, as well as Brampton, Mississauga, southern parts of Bruce County, Hamilton, Haldimand-Norfolk and all of southeastern Ontario.

Later this month, Ontario’s Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry will start hand-delivering rabies vaccine bait packets in urban areas within the control zone, including Kitchener and Brantford.

That will be followed by airdrops targeting forests and other remote areas. Airdrop activity will begin in late July, with greenspaces in urban areas being targeted in August and the Stratford area in September.

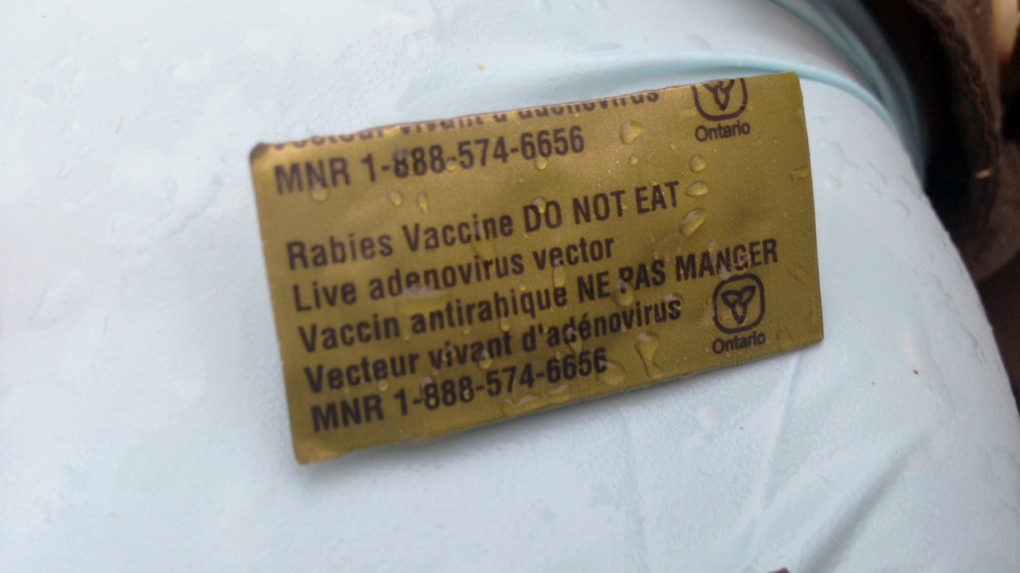

Anyone who comes across a bait packet in their yard, or anywhere else it is unlikely to attract the attention of wild animals, is being urged to only touch it with a plastic bag covering their hand, and to move the packet to a forest or similar area. Humans should not open, consume or directly touch the packet.

Last year, nearly one million of the packets were left around southern Ontario. More were airdropped in Huron-Perth in April.

Raccoons and skunks have been responsible for the vast majority of rabies cases during the outbreak, although the virus has also made its presence felt in bats, cows, cats, foxes and a llama.

No human cases have been reported in Ontario since the outbreak began.

The virus can be fatal to humans if it is not properly treated, and is typically fatal to animals. It can be spread through contact with infected animals such as bites, cuts or scratches.