True or false: "Canada is on track to meet its climate change commitments under the Paris Accord."

Your answer might depend on how you're getting your news, a new research project suggests.

In a climate of persistent fears that deliberate misinformation campaigns -- spearheaded by everyone from shadowy foreign actors to basement Twitter trolls -- could taint the legitimacy of this fall's federal election, a research effort called the Digital Democracy Project aims to analyze how information ricochets around the Canadian political landscape.

The project, led by the Public Policy Forum and the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University, will regularly survey Canadians about their political views and policy issues, review how journalists and political parties share information on social platforms and capture people's media use to produce reports on how news and information get digested ahead of the October vote.

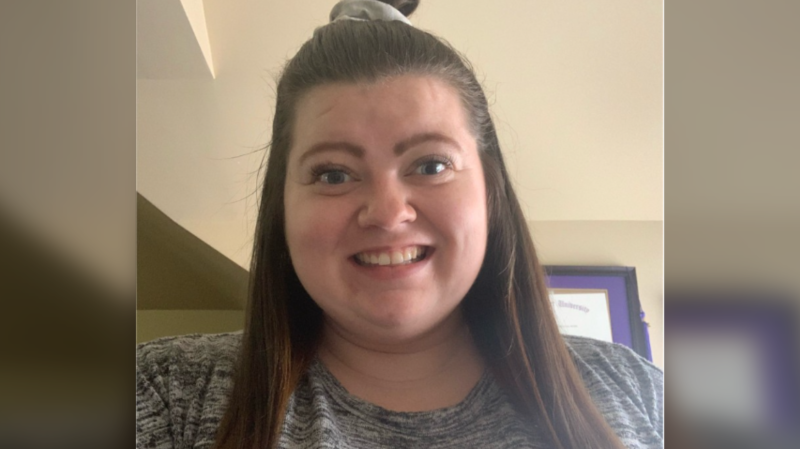

"We hope it can help us understand the relationship between what people are consuming, what they are exposed to and what they believe about politics in our country in this election," said Peter Loewen, a political science professor at the University of Toronto who led the analysis of the survey results.

Among other things, the first report released Thursday aims to set a baseline for how traditional media outlets stack up against social media in shaping Canadians understanding of topics up for debate.

In an online survey of 1,003 Canadians, conducted between July 24-31, researchers asked fact-based questions to see how the answers lined up against political affiliations and news consumption habits. The survey cannot be assigned a margin of error because online polls are not considered random samples.

On the Paris Accord question (the correct answer is "false"), 43.9 per cent of respondents answered correctly, 19.3 per cent got it wrong and 36.8 per cent said they were unsure.

That echoes the study's broader findings: Canadians are more likely to be uninformed than misinformed about a given policy issue.

Whether that means Canadians in turn will be more resilient against deliberate misinformation campaigns is a marker that researchers hope to capture in the coming months.

But the study reveals a difference in those numbers, depending on where people get their news.

Broadly, the research suggests that the more people are exposed to news -- be it traditional channels like the CBC or The National Post -- or via social media, the more they are likely to be wrong about the facts. And the more partisan a person, the more likely they were to give a wrong answer, especially if their main source of news was social media.

"The takeaway is that traditional media does a slightly better job of giving people more and better information the more they consume it, better than social media," said Loewen.

"But at least at the level of partisans, and as people are increasing their partisanship ... people consume media in a way that actually increases their misinformation, the more they are exposed and the more they are partisan. It's not a dramatic effect, it does not map onto the echo chambers we see in the United States, but it is an effect."