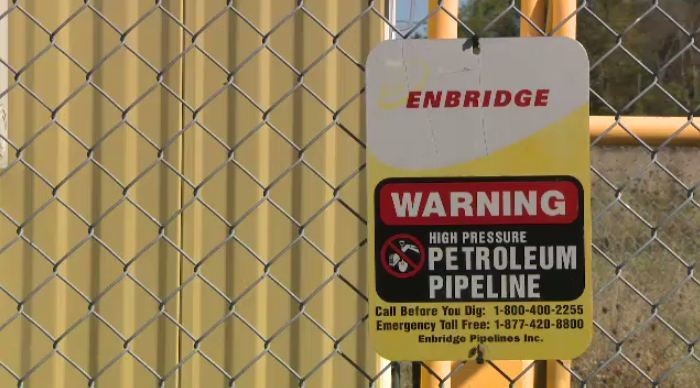

CALGARY -- In a field on the outskirts of Sarnia, Ont., there's a big blue wheel surrounded by a chain-link fence.

Attached to the fence and nailed to a nearby wooden post is a warning: high pressure petroleum pipeline.

Early one December morning, a trio of anti-pipeline activists managed to get to the other side of the fence. Photos show them smiling broadly as they turned the wheel, to which they then locked themselves.

While the incident caused no injuries or significant service disruptions, the owner of the pipeline -- the newly reversed and expanded Line 9 between southwestern Ontario and Montreal -- said that incident and others have raised "serious concerns."

"Enbridge sites are locked, secured and monitored for the safety of people and the environment. As with any vital infrastructure or service, they can be made dangerous if tampered with or sabotaged," said Graham White, a spokesman for Calgary-based firm Enbridge Inc. (TSX:ENB).

"We are assessing and employing various additional, permanent measures to enhance our security and safety at these sites to help prevent these types of tampering activities in the future. As part of ensuring the effectiveness of these measures, we will not provide details or discuss them publicly."

Lindsay Gray, speaking on behalf of the "land defenders" in an interview on the day of the Sarnia protest, said there wasn't much stopping them.

"Anyone could have done this," she said. "Anyone."

Line 9 was offline for about 90 minutes while the protesters were removed from the site and Enbridge inspected the line for damage. Though the protesters took credit for the shutdown, Enbridge says the line was shut off remotely from its control room.

There was a similar disruption two weeks earlier on another segment on Line 9 in Quebec. And then in early January, Enbridge's Line 7 near Cambridge, Ont., was shut down due to sabotage.

Kelly Sundberg, an associate professor at Mount Royal University who specializes in environmental crime, shakes his head at those tactics.

"It's just so dangerous," he said. "They risk causing damage to the line. There are so many possible negative outcomes that could come both from a security perspective, but also from an environmental damage perspective."

On that score, Gray retorted: "Every second that it's flowing, we're in danger."

Martin Rudner, professor emeritus at Carleton University who is an expert in security and critical infrastructure, said the industry has a variety of measures in place to secure their sites and respond when they are breached -- and generally they seem to be working.

"It's hard to make an overall judgment, but I think the best way to judge it is the fact that no major interruption has taken place," he said.

But, he said: "Needless to say, they can't be everywhere all the time."

Many companies hire security guards to patrol sites, but Rudner said the use of drones could be a much more effective approach -- though there are regulatory hurdles to that.

Warren Mabee, director of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy at Queen's University, said he sees the rash of pipeline tampering as a "blip," with the anti-pipeline movement emboldened by recent wins like the U.S. rejection of the Keystone XL project.

"It's not a good tactic. I think that it backfires because I think that the broad public, although they may not like the pipeline, they see that as beyond the pale."