TORONTO -- The downward spiral of despair to her untimely death began accelerating from the moment a troubled 15-year-old Ashley Smith, clutching a plush pink pig, entered a prison system poorly equipped to deal with the mentally ill.

Her crime: throwing crab apples at a postal worker.

Four years later, wedged between the steel cot and wall of her segregation cell, Smith took her last gasps as those entrusted to keep her safe watched and dithered, apparently rendered monstrously inert by orders from above.

As the exhausting, tortuous inquest into her death in October 2007 breaks for the summer at its half-way point, it has become obvious that many people in the prison system cared deeply about her, while others cared more about their jobs, advancing their careers or pushing paper.

Smith, we now know, was a mentally-ill girl who at times wanted to kill herself, at other times dreamed of getting married. Who could by turns be sweet and funny, aggressive and manipulative.

No one, it seems, knew how to deal with her.

"This was a train wreck that happened in slow motion," says Julian Roy, one of Smith's family lawyers.

"Everybody saw it happening, month by month, week by week. Many people foresaw the end of this case, yet everybody was paralyzed."

Over the past six months, the inquest under the steady hand of Dr. John Carlisle has heard from more than 50 witnesses: guards, a pilot, middle managers, psychologists, psychiatrists and nurses.

They came from most of the nine institutions in five provinces through which Smith, of Moncton, N.B., was shunted 17 times in the last year of a life that ended Oct. 19, 2007, in isolation at the Grand Valley Institution in Kitchener, Ont.

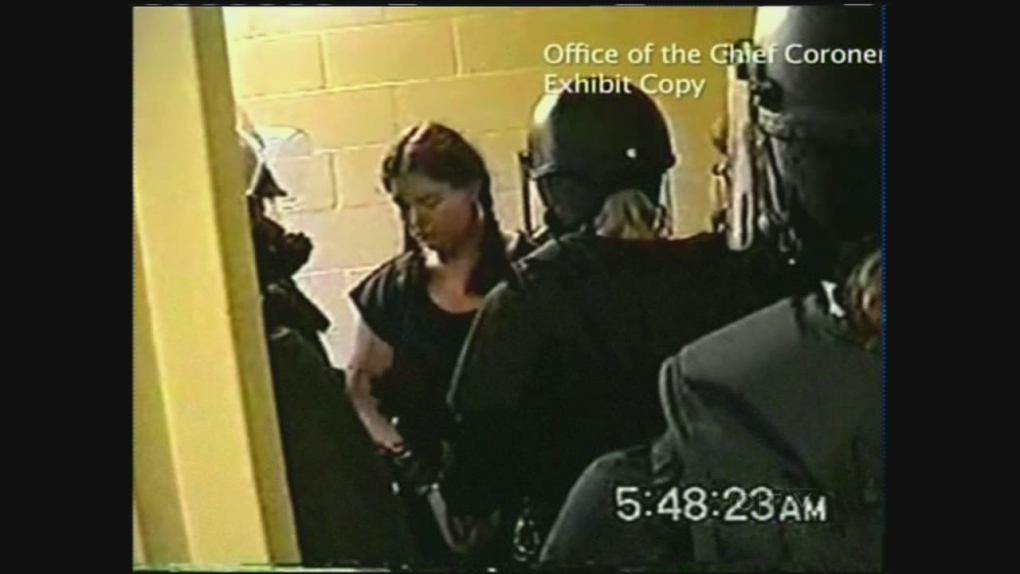

The five women jurors have viewed hours of haunting prison videos of Smith turning purple. They have heard her rattling breath from tying ligatures around her neck -- a propensity to self-harm that was part attention seeking, part desperation.

"Any person, never mind somebody who has serious mental-health issues, lodged in those extreme conditions of solitary confinement is going to break down," Roy says.

"She certainly deteriorated, as anybody would, in that situation."

Some witnesses wept on the stand at what they did or did not do and at what became of Smith. Some seemed curiously indifferent or evasive. Few took any responsibility.

Psychiatrists prescribed medication without seeing the teen. Psychologists made fitful attempts to offer some form of therapy -- through the food slot of her cell door.

The diagnosis, somewhere along the line, was that Smith suffered from severe borderline personality disorder.

Through it all, Smith was drugged against her will, pepper-sprayed for biting or scratching guards or being obdurate. She spent countless hours in a barren segregation cell, often with nothing more than a security gown designed to protect what was left of her dignity.

She was duct-taped to an airplane seat during one transfer -- "trussed up like an animal," as one of her family lawyers put it -- despite being docile.

RCMP pilot Cpl. Stephane Pilon, who ordered the duct-taping, was bluntly unapologetic, saying Smith posed an extreme danger to the aircraft.

Some, such as Grand Valley guard Blaine Phibbs, patiently spent hours with her, offering as much by way of caring and friendship as was possible as Smith, who came from Moncton, N.B., hurtled inexorably toward the abyss.

"You're going to seriously hurt yourself one day," he says to her at one point. "You want to hurt yourself?"

"No."

"What happens if we can't get that off you? What if it's too tight?"

"I won't die. I know what I'm doing," Smith would tell him.

Some of the medical professionals decided her problems were behavioural, leading to the notion that all she needed was punishment for misbehaving, rewards for the times she was compliant.

Senior prison management, concerned with showing superiors at regional and national headquarters they were running a well-oiled prison machine, appeared to adopt that view.

The inquest has heard how the warden and deputy at Grand Valley demanded reports be falsified. The aim was to play down incidents in which force was used against Smith, because the reams of paper generated were attracting the attention of, and pressure from, regional and national headquarters.

Jurors heard how managers reprimanded front-line staff for intervening to save a blue-faced Smith or harassed the chief psychologist for making recommendations that would have cost money.

"I called this a reign of terror," Cindy Lanigan, the chief psychologist, testified.

"This was a paramilitary organization where you don't go above your boss's head because it would come back to you."

For Smith's family, the inquest has already proven a key point: guards at Grand Valley were under orders to stay out of her cell as long as she was breathing.

"It is clear that that was the direction," Roy says.

Breese Davies, the lawyer who represents the Canadian Association of Elizabeth Fry Societies, says she believes one remarkable consensus has emerged, even at this stage of the inquest.

"(Smith) didn't belong in a correctional institution. She needed to be somewhere else," Davies says.

"That consensus is extraordinary from the different perspectives, and I don't think that perspective will change."

The inquest heard how many of Canada's female inmates need intensive therapy but treatment facilities are in woefully short supply. In fact, the country's lone psychiatric prison that takes female offenders -- the Regional Psychiatric Centre in Saskatoon -- had only 12 beds for women.

Smith was given one of those beds, but her stay was cut short after a guard was accused of assaulting her.

Smith's adoptive mother, Coralee Smith, testified her daughter was a happy, normal child until she entered her teens.

In a harrowing account of the last time she saw her daughter alive, Smith described her shock at the teen's appearance during the visit in the summer of 2007 at the Nova Institution in Truro, N.S.

"Oh, mom, my skin is all loose," Ashley told Smith through the Plexiglas screen that separated them.

"She was not a 19-year-old girl at that point, she was aged," Smith told the jury. "She was a lot smaller."

When the inquest resumes Sept. 9, a few more witnesses from Grand Valley, including the warden and deputy warden, will offer their views. In all, at least 50 more are slated to testify.

Ultimately, then, it will be up to the jury to make their findings as to what happened to Smith, and offer recommendations on how to prevent such a tragedy recurring.

"It's been a gruelling process," says Jocelyn Speyer, coroner's co-counsel.

"I don't think that anybody will have a concern that there's been a stone unturned."

Advertisement

System failings already evident at mid-point of Ashley Smith death inquest

The Canadian Press

Published Monday, July 1, 2013 6:54PM EDT

Published Monday, July 1, 2013 6:54PM EDT

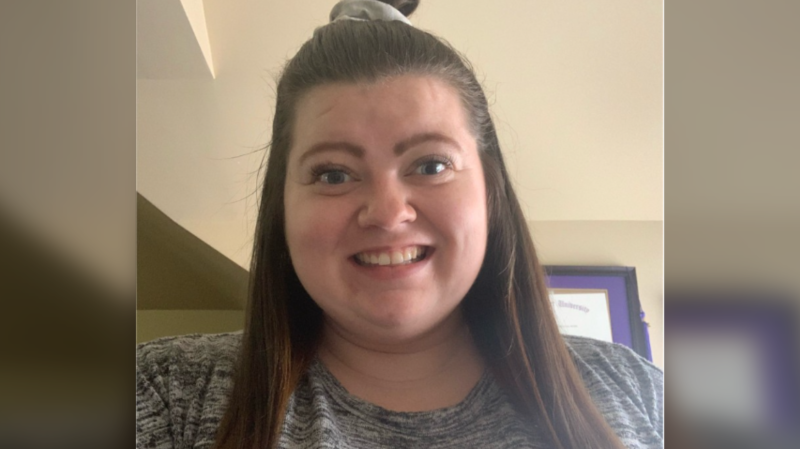

Ashley Smith is seen in one of the videos recorded by prison employees.