The family of a cancer-stricken aboriginal girl who abandoned treatment in an Ontario hospital in favour of traditional healing is blaming the death of their daughter on the side effects chemotherapy "inflicted on her body."

But doctors said the 12 weeks of chemo Makayla Sault received before leaving the hospital would not have been long enough to cause serious harm.

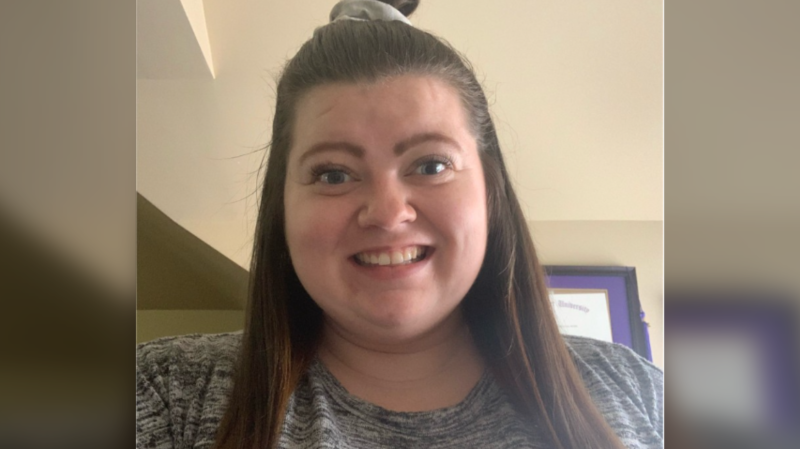

The case of the 11-year-old member of the Mississaugas of the New Credit First Nation, located near Brantford, Ont., made headlines last year when she announced her decision to abandon her cancer treatment.

Sault suffered a stroke on Sunday and died on Monday, her family said, calling her death "tragic."

"Makayla was on her way to wellness, bravely fighting toward holistic well-being after the harsh side effects that 12 weeks of chemotherapy inflicted on her body," her family said in a statement issued in the Two Row Times, a weekly newspaper covering indigenous issues.

"Chemotherapy did irreversible damage to her heart and major organs. This was the cause of the stroke."

An oncologist countered, however, that untreated leukemia can in fact cause strokes.

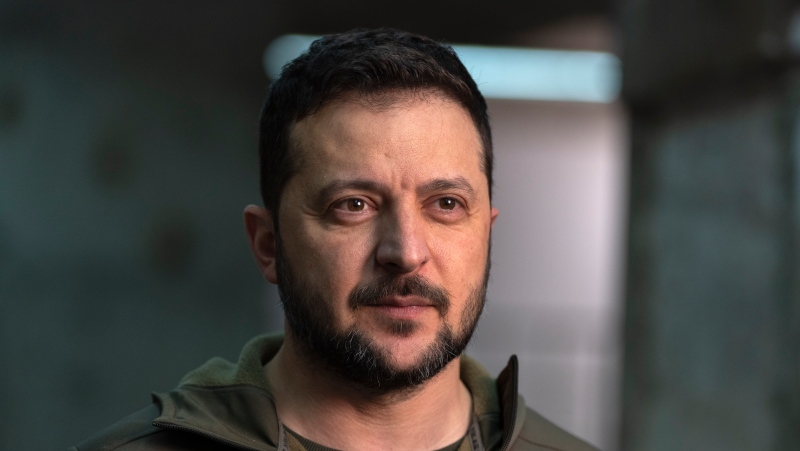

A leukemia cell could go into the bone marrow and crowd out normal cells, leading to a very low platelet count which could result in a bleeding stroke in the head, explained Dr. Jacqueline Halton, a pediatric hematologist-oncologist at the Children's Hospital of Eastern Ontario.

Alternatively, leukemia could cause a patient to have a very high white cell count, which could also lead to a stroke, she said.

"If your white cell count is so high, it can make the blood very sludgy," she said. "You can have a stroke from the blockage of the arteries in the brain."

Halton added that while certain forms of chemotherapy can possibly lead to a stroke, that would happen within days or weeks of receiving chemotherapy, not months after it was stopped.

Chemotherapy does, however, result in a host of unpleasant side-effects which would disappear when a patient stopped the therapy, Halton noted.

"It's a multi-agent therapy so absolutely as soon as you come off these agents, you are going to feel better until that leukemia rears its ugly head again," she said, noting that chemotherapy has a 90-per-cent cure rate for leukemia.

Sault wrote a letter last year saying she had asked her parents to take her off chemotherapy because the treatment was "killing" her body.

"I was sick to my stomach all the time and I lost about 10 pounds because I couldn't keep nothing down. I know that what I have can kill me but I don't want to die in a hospital on chemo, weak and sick," she wrote.

The McMaster Children's Hospital in Hamilton, which had administered chemotherapy to Sault, offered its condolences to her family.

"Everyone who knew Makayla was touched by this remarkable girl. Her loss is heart-breaking," hospital president Peter Fitzgerald said in a statement. "Our deepest sympathy is extended to Makayla's family."

Sault's parents took their daughter to a hospital after she had her stroke on Sunday but brought her back home after she had been examined by doctors, said Bryan LaForme, chief of the first nation the family is part of.

LaForme added that Sault's firm stance on the way in which she wanted to be treated would be well remembered.

"I think she will be remembered partly as a trailbrazer," he said. "She set the course for a court action that worked in the favour of First Nations across the country."

That court action involved a case in Ontario very similar to Sault's, where another aboriginal family opted for alternative therapy to treat their daughter for cancer.

That case, which also involved the McMaster Children's Hospital, ended up in court when the hospital sought to have the child apprehended and placed back into chemotherapy after her mother pulled her out of treatment.

The child's mother took her to Florida for alternative therapy, which involved herbal treatments and lifestyle changes.

An Ontario judge ruled in November, however, that doctors could not force the girl to resume chemotherapy.

The decision didn't prevent the girl from seeking treatment in a hospital in the future but recognized the right of the family to treat the girl with traditional aboriginal medicine.

The family of the girl, who cannot be named under a court-ordered publication ban, sent their condolences to Sault's family.

"We mourn your loss," the family said in a statement issued in the Two Row Times. "I offer you strength to endure through your dark time. That one day you can adjust to the loss in your family circle."