TORONTO -- Students may not get the value they should out of increasingly more expensive university degrees if they don't specialize on fields in high demand, according to a new report.

The report by CIBC World Markets says that while completing a post-secondary education is still the best route to a well paying, quality job, the premium is dropping as too few students are graduating from programs that lead to good jobs.

"Narrowing employment and earning premiums for higher education mean that, on average, Canada is experiencing an excess supply of post-secondary graduates," said CIBC economist Benjamin Tal.

"And despite the overwhelming evidence that one's field of study is the most important factor determining labour market outcomes, today's students have not gravitated to more financially advantageous fields in a way that reflects the changing reality of the labour market."

Tal says students will get the biggest bang for their educational buck from specialized and professional fields such as medicine and law.

The fields of humanities and social sciences, on the other hand, carry much greater risk, while students in health or business face a more limited risk of ending up with lower incomes.

Yet the study found just under half of recent graduates fall under the sectors deemed "underperforming" -- even though they know they'd earn more with a medical or law degree.

"Canadian students are continuing to pursue fields where upon graduation, they aren't getting a relative edge in terms of income prospects," said Tal, who co-authored the report.

The unemployment rate among university graduates, he adds, is just 1.7 percentage points lower than among those with only high school education, a gap that was much larger in the 1990s.

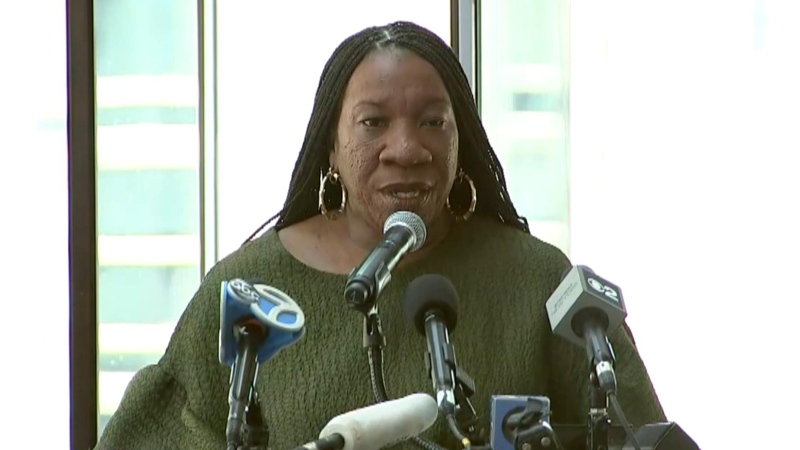

Jessica McCormick, chairperson for the Canadian Federation of Students, says that some students are discouraged by how difficult it can be to find a job in their chosen field upon graduation, especially with the added stress of having to make student loan payments.

But she also argues that it's important to have people with a variety of training, because areas that are in high demand right now may not be 10 years down the road.

"If students were all studying in a particular field, that would obviously saturate those fields of study and return on investment would decline because there would be more competition for jobs," McCormick said.

"We've seen that happen over the years in education for example."

Students should also have flexibility to study in the areas they're most interested in, she said, and to opt for the degrees with lower tuition, especially given that the average student will graduate university with $28,000 in debt.

"What we really need is a more flexible and accessible system of post-secondary education that's affordable, that allows people to shift between fields while they're in study, to train or retrain as market demands change, and right now, it's quite difficult to do that because of high tuition and high student debt," said McCormick.

"It deters people from switching fields or upgrading their training or continuing on to graduate level studies which will likely have better outcomes from them in terms of finding a job and getting that return on investment."

According to the CIBC study, which examined various reports that have attempted to compute an annualized average "return on investment" on education and found stark divergences depending on the field of study, the university premium over college has also narrowed and now comes to 0.7 percentage points.

Masters degrees or PhDs signal more specialized skills than a bachelor's degree, but that hardly translates to unemployment statistics, with the jobless rate premium falling to just 0.5 percentage points.

Overall, higher education still translates into better wages -- those with a bachelor's degree, on average, earn more than 30 per cent more than high school graduates. While masters or PhD graduates have a 45 per cent earnings premium over those with secondary degrees.

CIBC also found that real weekly wages of high school and college graduates have risen by 13 per cent versus eight per cent among undergraduate degree holders and more than double the rate seen among MA and PhD holders.

The share of part-time work among university-educated Canadians also rose from 10 per cent in the 1990s to 13.5 per cent today, with the gap relative to high-school graduates narrowing to only one percentage point.

Tal believes that improving participation rates in high-demand fields will likely require finding a way to identify emerging trends in labour market needs, as well as improved quality and equity of learning opportunities and increased resources.

He also sees a need for simpler and efficient credential recognition process for new immigrants, and better access to language training.

The Association of Universities and Colleges of Canada, for its part, said Canadian universities are experiencing record levels of student enrolment, with 793,000 full-time and 234,000 part-time undergraduate students enrolled in universities in 2012.

It also notes that according to a Statistics Canada Labour Force Survey, from July 2008 to July 2013, the net increase in new jobs for university graduates was 810,000, while the available jobs for those with no post-secondary education decreased by 540,000 during the same period.